You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

My university’s decision to slash ‘housing studies’ is a huge blow to the sector

The government has acknowledged that housing needs to be included as a subject requiring specialised training and knowledge, so why are universities abandoning teaching housing, asks Glyn Robbins, senior lecturer in community development and leadership at London Metropolitan University

In 1991, I went from being a housing benefits officer for Newham Council to studying a master’s course in housing at the London School of Economics (LSE). It was life-changing.

I worked in housing for the next 30 years, in a wide range of different roles. It was the LSE course that laid the foundation for my housing career. Along the way, I had some amazing experiences I would never have had otherwise.

In 2022, after 10 years managing an Islington council estate, I left the housing coalface for a job at London Metropolitan University. I share my knowledge and experience with students, some of whom might want to pursue a career in housing or a related field, but all of whom are interested in knowing more about a subject that has rarely had such widespread social impact.

I do a class I call “The Housing Matrix”. In this word association exercise, I write the single word “HOUSING” on a big sheet of paper and invite students to list all the issues that flow from it. Within minutes, they fill the space with a multitude of highly relevant topics that illustrate the pervasive influence of housing in today’s society.

When I was at the LSE, it was one of numerous colleges and universities where housing was taught as a dedicated subject, with many also offering a route to membership of the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH). Today there are virtually none. London Met is one of the few remaining, but it is also planning to abandon housing studies.

Mine is one of 120 redundancies of teaching staff the university wants to make, claiming a financial “crisis”. Leaving aside the highly dubious justification for these savage cuts, dropping housing is an act of folly.

The Social Housing Regulation Act 2023 now requires people working at a senior level to hold a recognised qualification. The students who pass London Met’s housing courses meet this requirement, giving them an immediate advantage in the housing job market.

“Many of my students also have first-hand experience of the housing issues we discuss in class. When we talk about the difficulties of homelessness, temporary accommodation, high rents and disrepair, they nod knowingly”

Most of the people I teach at London Met come from “non-traditional” academic backgrounds. Many of them combine study with work, and often childcare. They highly value the potential of finding reliable, reasonably well-paid and stimulating employment. Studying housing provides that opportunity.

Many of my students also have first-hand experience of the housing issues we discuss in class. When we talk about the difficulties of homelessness, temporary accommodation, high rents and disrepair, they nod knowingly. If “knowledge is power”, then teaching housing is one way towards the fundamental change in housing policy we desperately need.

Sadly, London Met doesn’t see it this way. The financial lure, precipitated by the introduction of tuition fees in 1998, has led to the wholesale commodification of further and higher education.

In this sense, the sector bears some similarities with the housing world since the promotion of commercially oriented corporate housing associations. Like some social landlords, universities have forgotten their social purpose.

“Having properly qualified housing workers can be a matter of life or death”

While pursuing lucrative overseas students, property deals and mergers, universities like London Met ignore their traditional base. Unlike “elite” universities, London Met has long recruited a large number of students from its immediate area. It specialises in teaching vocational courses, leading to work in essential public services.

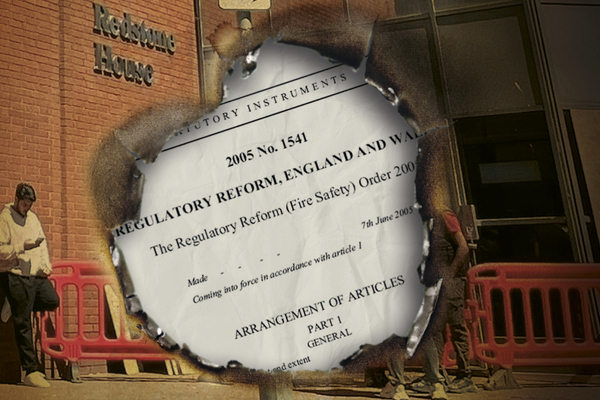

Following Grenfell and Awaab Ishak, the government has acknowledged that housing needs to be included in university curricula as a subject requiring such specialised training and knowledge. Having properly qualified housing workers can be a matter of life or death.

I warn my students that housing work isn’t glamorous and unless you become chief executive of a housing association, it won’t make you rich. It’s rewarding in other ways. In an increasingly impersonal world, at root and when it works best, it relies on face-to-face human relationships.

I also tell them most of what’s needed to do the job well is common sense. However, there is also a need for some specialist knowledge and skills. Some of this can be learned in other places, but universities enable students to exchange ideas and experiences, while developing the kind of critical thinking that is absolutely vital in a field where hierarchy and orthodoxy can lead to disastrous outcomes.

Instead of dumping housing studies, London Met should be joining other universities in promoting the subject at a time when “doing it right” has never been more important.

Glyn Robbins, senior lecturer in community development and leadership, London Metropolitan University

Sign up to Inside Housing’s Daily News bulletin

Sign up to Inside Housing’s Daily News bulletin, featuring the latest social housing news delivered to your inbox.

Click here to register and receive the Daily News bulletin straight to your inbox.

And subscribe to Inside Housing by clicking here.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.

Related stories