You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

What do councils need to properly house asylum seekers?

The government should redirect the money spent on asylum accommodation into secure homes for everyone, writes Tim Naor Hilton, chief executive of Refugee Action

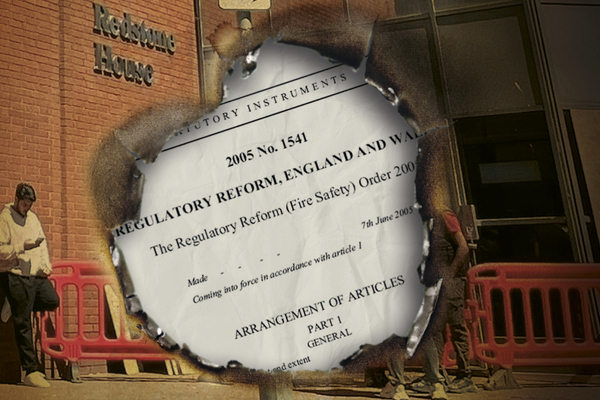

For decades, successive governments have pursued policies that have created an acute – and worsening – housing emergency. The snowballing privatisation of our homes has decimated social housing and left councils unable to properly respond to need within their communities.

A safe and secure home is not only fundamental to our health, well-being and sense of place, but vital for inclusive, resilient and prosperous towns and cities. That is why this emergency is felt so deeply by people who find themselves at the end of a social housing list, or homeless, or unable to afford a deposit to buy a home.

People seeking asylum feel the consequences too, as they stare down far-right violence from a dingy hotel, a decrepit house in a segregated neighbourhood or an army camp. Whoever is at the sharp end, the fallout is incredibly expensive.

Temporary housing costs councils almost £3bn a year, according to the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, while the Home Office pays a murky web of private contractors and subcontractors £1.5bn a year to find beds for people seeking asylum.

Our new report, Laying the foundations, argues that the government should redirect this money to communities to build homes and fund councils to run one housing system for all people in need.

We asked 38 councils and dozens of other stakeholders what they thought was needed for a locally run system to house people seeking asylum – such as that proposed by the Institute For Public Policy Research, the Commission for the Integration of Refugees, and others – to be workable.

What emerged was a feeling that, with the right conditions, a joined-up model could be better value for money and would improve outcomes for people seeking asylum, for local authorities and for communities.

Councils were understandably cautious about the practicalities, and repeatedly said that any change must be properly resourced, clearly governed and phased carefully. Specifically, they told us that government needs to create several conditions to make sure a locally delivered model can be successful.

“With the right conditions, a joined-up model could be better value for money and improve outcomes for people seeking asylum, for local authorities, and for communities”

First, there needs to be a massive programme of building, buying and converting homes to build back social housing stock for councils and social landlords that can house people in need.

Local authorities we spoke to favoured a capital grant scheme – such as that proposed by Soha Housing’s Kate Wareing – to fund the purchase and renovation of housing for social use. Funding to repurpose underused commercial property was also supported.

Secondly, councils want government to work with them to build a new system, with clearly defined local and national roles, accountability, data sharing and, critically, comprehensive and long-term funding agreements.

Next, they want ministers to reform the dispersal system so responsibility for welcoming and supporting people seeking asylum is shared fairly across the UK.

Finally, government must stop demonising people seeking asylum to reduce toxicity and recognise that improving the asylum system is an opportunity to invest in our towns and cities.

Councils told us that community engagement would be critical to the success of a decentralised system, with a large majority viewing local partnerships and investment in staffing as the best ways to support readiness.

With these foundations in place, councils saw that investing in homes and rebuilding local capacity could renew communities and demonstrate that inclusion and efficiency go hand in hand.

“Decades of austerity, the decimation of social housing and a toxic climate caused by the hostile environment have left many councils unable to take on more responsibility”

As one local authority officer told us: “When councils have control, we can align asylum housing with other priorities – like addressing homelessness or improving community services. That kind of joined-up thinking just isn’t possible under the current system.”

With the current political realities, reform won’t be easy. How we support refugees has been turned into a toxic issue, a toxicity that has been enabled and encouraged for decades by successive governments. It has led to migrants being scapegoated for problems they themselves are affected by.

Change will take courage and time, but it is necessary and urgent. Decades of austerity, the decimation of social housing and a toxic climate caused by the hostile environment have left many councils unable to take on more responsibility.

Communities are being denied billions of pounds of public money that is instead lining the pockets of directors and shareholders. So let’s change that, to fundamentally tackle the housing emergency, invest in communities and work with councils to design a unified system that supports all people in need of a home.

Tim Naor Hilton, chief executive, Refugee Action

Sign up to Inside Housing’s Homelessness newsletter

Sign up to Inside Housing’s Homelessness newsletter, a fortnightly round-up of the key news and insight for stories on homelessness and rough sleeping.

Click here to register and receive the Homelessness newsletter straight to your inbox.

And subscribe to Inside Housing by clicking here.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.

Related stories