You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Awaab’s Law update: landlords’ most common questions answered

Awaab’s Law came into force on 27 October, mandating major changes to how social landlords respond to repairs. Paul Lloyd, housing management partner at law firm Capsticks, answers landlords’ most common questions about the regulatory change

Learning outcomes

- Understand how to approach instances of ‘no access’ in the new context of Awaab's Law

- Understand the requirements around providing a ‘written summary’ of an investigation, including when and how to provide one and what to include

- Learn what to do if additional remedial works are required which fall outside of the Awaab’s Law regulations

- Understand who should investigate when a hazard is reported

- Recap the Awaab’s Law regulations, including timelines for implementation, types of hazards and key obligations

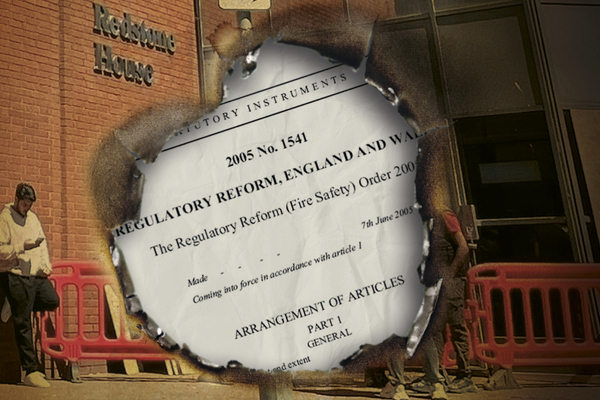

Awaab’s Law is a landmark UK housing reform which was introduced in 2023 through the Social Housing (Regulation) Act. It came into force on 27 October.

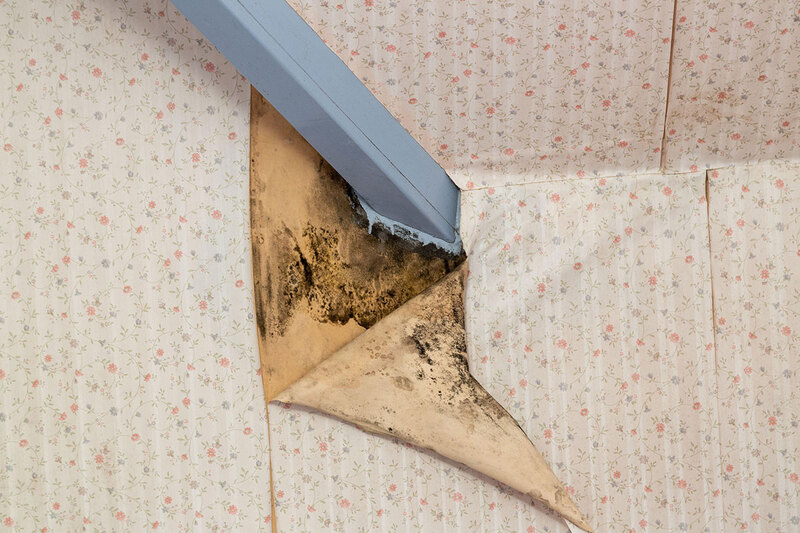

Named in memory of Awaab Ishak, who died at the age of two from a respiratory condition caused by prolonged exposure to mould in his home, the law aims to prevent similar incidents by enforcing stricter standards for social landlords.

This includes setting legal deadlines for landlords to investigate and address hazardous conditions in tenants’ homes through the Hazards in Social Housing (Prescribed Requirements) (England) Regulations 2025 – referred to in this article as “the regulations”.

This article answers several of the most common questions that landlords are asking in relation to Awaab’s Law, and you can scroll down if you need a recap on the regulations themselves.

What should a landlord do if they are not able to gain access?

Section 20 of the regulations implies a provision within social housing tenancies that a tenant must allow access to the landlord (or a person authorised in writing by the landlord) to enter their property to comply with the regulations. Access should be allowed at reasonable times of the day, but only if at least 24 hours notice has been given in writing.

Landlords should also read the tenants’ guide to the regulations, which outlines expectations on landlords when arranging access. These include considering time slots for access, contacting the tenant in a way that suits them, explaining why access is required and offering support in relation to who will access the property. The landlord should also leave a note if they miss the tenant.

On the basis of the above, if they have not already done so, landlords should review policies and procedures on accessing a tenanted property. Landlords need to make sure that employees and contractors understand the need to keep detailed records of efforts to access properties, as per their obligations under the regulations, and to show that they have tried to engage with tenants to work with them to get access.

When and how does a landlord provide the required written summary following an investigation?

The written summary must explain whether the investigation identified a significant or emergency hazard, what it was and what action is required, and provide target timeframes for beginning and completing any required actions.

Equally, if no further action is necessary, the written summary must specify that there is no action required under the regulations, and outline the reasons why no action is required.

The summary must include information on how to contact the landlord.

The summary must be provided within three working days, beginning on the day after the date that the investigation is completed.

A summary is not required if identified remedial works are completed before the three working days expire.

The summary can be handed to the tenant, left at the tenanted property, sent by first-class post or next-day delivery, or sent electronically to an address or mobile provided by the tenant to the landlord for communication about the tenancy.

Who should investigate when a hazard is reported?

As for who should investigate reported hazards, the regulations reference “a competent investigator”, defined as: “A person that, in the reasonable opinion of the lessor (landlord), has skills and experience necessary to determine whether a social home is affected by a significant or emergency hazard”.

Given the defined meanings of significant and emergency hazards, and the need for “relevant knowledge” of the health and circumstances of the occupier (see Key obligations below), it is important that the role of investigator is given proper consideration along with the identification of the specific hazard.

How do the changes sit with the current pre-action protocol for property condition claims?

If a tenant or their solicitor reports a hazard that is believed to fall within the Awaab’s Law regulations, a landlord must investigate in line with the regulations and complete the required works to comply with them. Keeping detailed records is important to show compliance.

It may be that other works are also required that fall outside of the regulations. In this case, provide evidence, and consider when the works will be completed, so the tenant can be kept informed. Transparency is a key theme of the regulations and also of the consumer standards.

Awaab’s Law: a recap on the regulations

A phased approach

Awaab’s Law is being implemented in three phases: Phase 1 (October 2025) focuses on emergency hazards, in addition to damp and mould; Phase 2 (2026) extends the regulations to excess cold and heat, falls (accidents that can occur in baths, on level surfaces, on stairs or between levels), structural collapse and explosions, domestic and personal hygiene and food safety; finally, Phase 3 (2027) covers all remaining hazards in the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS), except overcrowding.

Types of hazards

The law defines hazards based on their risk level. Emergency hazards must be addressed within 24 hours. That includes both the investigation and the “relevant work”.

Significant hazards must be investigated within 10 working days of landlords becoming aware of them, and “relevant work” commenced within five working days of the investigation concluding.

The definitions of “significant hazard” and “emergency hazard” are outlined in Section Three of the regulations.

Key obligations

Landlords are required to provide tenants with a written summary of findings within three working days of the completion of a relevant investigation into a hazard, beginning on the day after the investigation is completed.

The regulations make it very clear that tenants’ personal circumstances are an important factor when considering the risks they face, as the law takes into consideration “knowledge that a lessor (landlord) of the social home has, or reasonably ought to have, about the health and circumstances of the occupier”.

Landlords therefore cannot adopt a one-size-fits-all approach, but must consider specific vulnerabilities of different occupiers which could put them at risk from different hazards. They need to maintain accurate information about tenants, which they can then apply during a risk assessment.

Tenants will be able to apply to the County Court for an order for specific performance (works to be completed) if they believe a landlord has failed to comply with their obligations.

However, to protect landlords in no-access cases, there is an implied covenant that a landlord (or someone authorised in writing by the landlord) may enter the home for the purpose of complying with their obligations.

Record-keeping is as important as ever if a landlord wants to show that attempts at access to investigate or complete works have failed. Copies of appointment letters, recorded attempts at contacting the tenant by any means possible, and any resulting no access cards will be of the utmost importance in proving failed access attempts.

Detailed record-keeping in the wider context of tenancy management will allow for speedier investigations to establish which works fall within the scope of the regulations and which do not.

It should be noted that, under the regulations, relevant works do not cover works required as a result of a tenant failing to use the property in a “tenant-like manner” (the government’s wording). Landlords must therefore be aware of not only their own obligations, but those of the tenants, under the terms of their tenancy agreements.

Overall, landlords are encouraged to adopt a proactive approach, maintain clear documentation, and respond swiftly to tenant concerns. The phased rollout also allows for a ‘test and learn’ approach, enabling adjustments based on feedback from housing providers.

Further guidance

To help landlords comply, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) have issued guidance for landlords and tenants, to be read in conjunction with the regulations and consumer standards.

Subscribe to Inside Housing Management and sign up to the newsletter

Inside Housing Management is the go-to source for learning, information and ideas for housing managers.

Subscribe here to read the articles.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.

Related stories